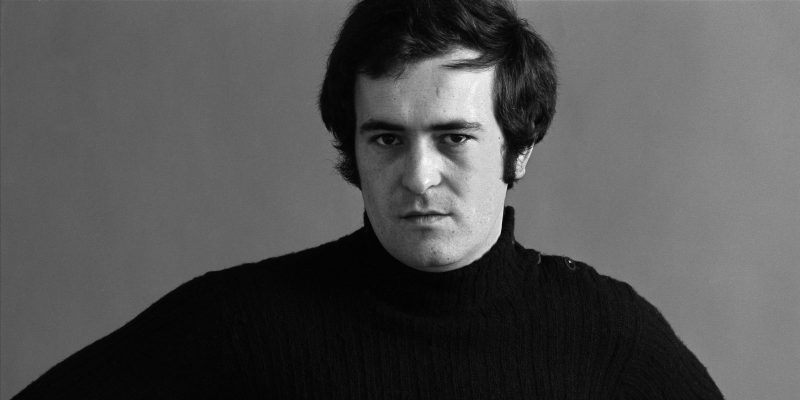

BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI – A LIFE IN ACTS

This is something that I dream about: to live films, to arrive at the point at which one can live for films, can think cinematographically, eat cinematographically, sleep cinematographically, as a poet, a painter, lives, eats, sleeps painting. – Bernardo Bertolucci

He was a maestro, a director par excellence. One of the pioneers of the New Wave Italian Cinema along with Fellini, Visconti and Pasolini.

“First of all, we lost a poet. And there are not so many poets in the world, they are born three or four in a century”.

Alberto Moravia spoke of Pier Paolo Pasolini at his funeral. 40 years later, these words would also be true for Bertolucci.

The Italian director was an undisputed legend in his craft. The most international and recognized name of the last great generation of Italian cinema, think-Traviani, Bellocchio, Rosi, Olmi and Pietri. He was the heir to the new 60’s vogue of the politically committed cinema of the time. But above all, a movie poet, creator of memorable images that filtered a unique sensitivity.

CRITICAL – SENSUAL – INTELLECTUAL – TRANSGRESSIVE

ACT I

Son of a teacher and a poet who was also a journalist and film critic, Bertolucci was born in Parma, Italy in 1941. When he was a little boy, his father gave him a 16mm camera which would mark his destiny.

In 1962 Bertolucci won the Viareggio Prize for poetry, but it was too late: cinema would forever be his obsession. For his second film, he left the Pasolinian shadow and adapted Stendhal freely. Before the revolution, follows the political and sentimental journey of a left-wing, young Italian bourgeois that begins an incestuous relationship with his auntie…

Great literary authors inspire him: Dostoevsky for Partner (1968), Borges in The Spider’s Stratagem (1978) and Moravia in The Conformist (1970). The last two – consolidated him as a reference of European cinema, sharing the themes of betrayal, the weight of the past and the Freudian subconscious, as well as an implacable revision of fascist Italy. In The Spider’s Stratagem, the protagonist discovers that his father, martyr of the anti-fascist movement, actually collaborated with fascism. The Conformist, on the other hand, follows the path of a frivolous man marked by the family trauma. In that trauma, fascism finds the perfect vehicle as he yearns for normality.

ACT II

The diptych also marks the beginning of the collaboration with the director of photography Vittorio Storaro, a master of the light that materializes the aesthetic dimension of the cinema of Bertolucci.

“Storaro is the brush, Storaro is the colour, Storaro is the hand of the painter that I am not or nor will I ever be.” Bertolucci acknowledged. The relationship between both is a constant stir-and-hurry, but the conflict goes hand in hand with works like The Last Emperor (1987) and Last Tango in Paris (1972). The second film evidently marking the beginning of his international career. Touched by the visual influence of Francis Bacon, the film is both an erotic fantasy and the nihilistic exorcism of a mature man who has just lost his wife. Paul, is Marlon Brando in his 40’s Bernardo Bertolucci undressed the technique of the Actor’s Studio to extract a most visceral and personal interpretation by Brando. The film transcended cinema thanks to its unleashed eroticism, but to see it in certain parts of the world, people had to pilgrimage to remote cinemas which welcomed buses full of spectators inflamed with a morbid curiosity.

The most tone-up scene, in which Brando sodomized a young Maria Schneider, went into history because of the sexual cruelty, then because Schneider denounced the scene stating she was, manipulated by Bernardo Bertolucci, leading to Brando raping her. The director always denied it, but still, it is difficult to see the film without feeling, at least, some kind of discomfort.

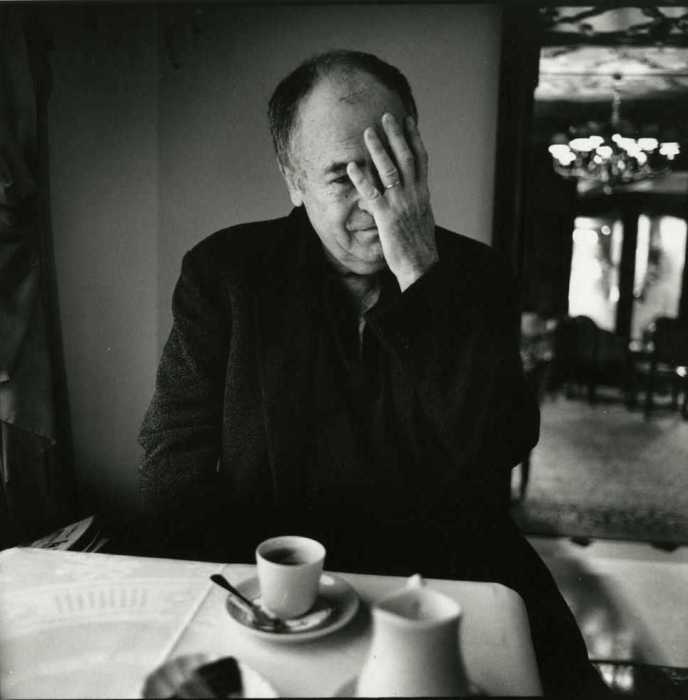

ACT III

To escape the controversy and the trials of Last Tango in Paris, the director returned home to roll a historic fresco of Italy in the first half of the twentieth century. But Bernardo Bertolucci is already a global author, nominated for an Oscar and of international prestige. The project, Novecento (1976), will feature an international cast including; Robert De Niro, Gérard Depardieu and veteran Burt Lancaster. A monumental project (the version premiered in Cannes 320 minutes) with a Marxist inspiration but produced by a Hollywood studio: an ideological betrayal that had already been reproached by his youthful idol, Godard, who after seeing the film remained with Bertolucci and, without exchanging any words, gave him an image of Mao with the phrase “Fight against imperialism!” written behind it. Decades later, Bertolucci remembered it humorously in the History of the Cinema by Mark Cousins. “I’d love to have kept the photo” he said.

ACT IV

In 1979 Bertolucci once again scandalized audiences with La Luna, a film about an incestuous relationship between a mother and her drug-addicted son. And in 1987, the unexpected arrived: The Last Emperor, his portrait of Pu Yi, the almighty emperor who eventually became a gardener in Communist China. The film won 9 Oscars. Hollywood blesses this epic movie of sumptuous beauty that unites the historic fresco with the intimacy of studying a character – from prisoner to his place in history. A beautiful and free adaptation of Paul Bowles, The Sheltering Sky (1949), and the blockbuster The Little Buddha (1993), completes his exotic trilogy. After he returns to Italy to portray Liv Tyler’s juvenile exuberance in Stealing Beauty (1996). The turbulent relationship between a pianist and an exiled African. The revolutionary nostalgia of The Dreamers (2003), with homage to Godard, included (the cinema of cinephiles). The most sincere and humble movie of this final stage is perhaps the latest, Io e Te (2013). It summarizes the director’s cinema in the stunning scene of the two leading brothers dancing embraced by Bowie’s Space Oddity (1969) in Italian version.

“Il n’y a pas d’amour, il n’y a que des preuves d’amour” is a line from Jean Cocteau in Robert Bresson’s movie Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945). A line that Bertolucci resumed repeatedly in his films.

Bernardo, your cinema is a proof of love to the world.